The Gateway to Maine’s North Woods

In the early morning hours of a Monday in October, 1998, a group of Maine woodsmen and environmentalists put a plan into operation. Climbing into vans and pickup trucks, they began the more than two hour drive from Allagash, Maine along an unpaved logging road to the Canadian border crossing near St. Pamphile, Canada. They had spent the previous two nights at a hunting lodge in Allagash, keeping a low profile so as not to alert the authorities or wood mill owners of their presence. In sparsely populated Aroostook, groups get noticed. For their plan to succeed, they needed an element of surprise.

Now tired, with little sleep, the group made their way through a dark Maine night and a late autumn snowfall. Large snowflakes tumbled from a black sky, appearing as a thousand points of light rushing at them in the van’s headlights. The drivers adjusted their speed to the night. Their eyes focused on the winding road as the dark forest raced by. The passengers were lost in their thoughts.

The spirit of comradery was high; loggers and environmentalist joining forces in the same cause was uncommon in the Maine woods. One group’s purpose was to preserve a forest; the other’s was to preserve their jobs. The two causes have different trajectories but crossed on this particular night.

Maine’s loggers have had a four decade long grievance with the state and federal governments concerning their claim that Canadian woodsmen were taking their jobs. They alleged that government officials were failing to enforce immigration laws dealing with foreign work visas. This, and the current exchange rate, allowed Canadians to enter Maine, work for a lower wage, and take jobs away from Mainers.

The group reached the border crossing at 4:45 AM, fifteen minutes before the border patrol opened its gate. The caravan had made it in time. Canadian woodsmen were already lined up on the other side, ready to enter Maine on their way to a logging job site.

At five minutes after the hour, the Mainers and environmentalists were in place. Their trucks had been strategically parked across the road on the U.S. side of the border. The group approached the gate and announced to the Border Guards and Canadians waiting to cross, they were blockading the border. No logging trucks or loggers would be allowed to cross. The border was shutdown.

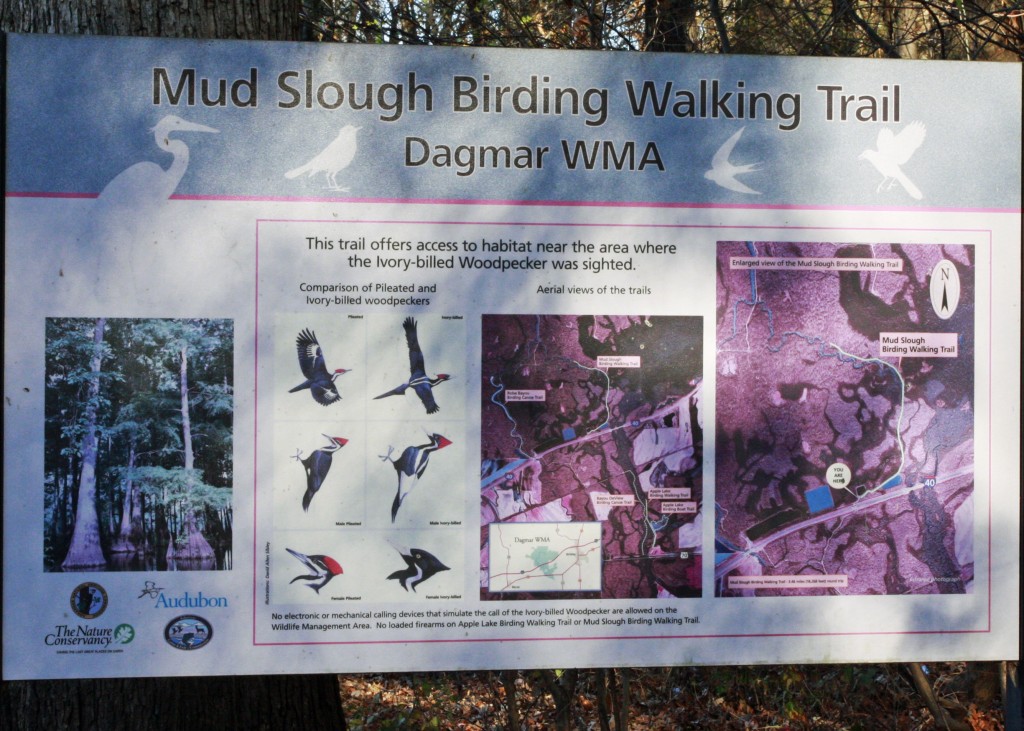

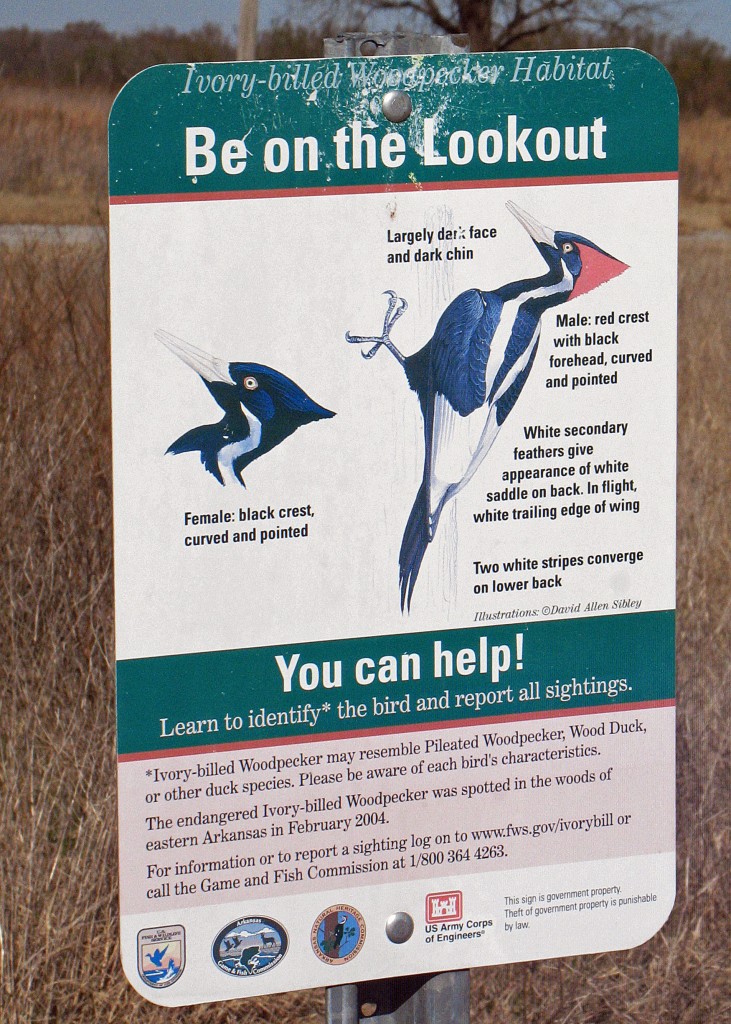

Border Crossing into St. Pamphile, Canada. Note the Canadian lumber mill and the U.S. Border crossing complete with building, personnel and security equipment. What is the cost to the U.S. tax payer to supply Maine lumber, logged by Canadian woodsmen, to a Canadian mill?

The local press covered the event, but not the national media. At the time, the nation was hungry for stories of President Clinton’s impeachment and the Monica Lewinsky affair. Today, news records of the event are as scarce as they are lacking in detail.

The Blanchet-Maibec Road is long, unpaved and a proven destroyer of tires. It’s also a toll road.

Later that month, a meeting to discuss the logger’s complaints was held in Presque Isle, Maine. It was attended by U.S. Sen. Susan Collins and U.S. Representative John Baldacci (later elected Governor) and other state officials. No solutions came from the meeting, only a promise to investigate the claims. Rep. Baldacci promised to look into the allegation that Mainers were being discriminated against by the mills and landowners: “We will try to find out if aggressive means were used to find Americans to work in the Maine woods before the Department of Labor turned to approving bonds for Canadians.” It was less than demanded, and less than hoped for, but it was enough to end the blockade. In the end, however, nothing changed.

Thirteen years later, I sat with a Maine woodsman who I’ll call John Miller. We were in a tavern in northwestern Maine, 30 miles from the Canadian border. The tavern was adorned with New England Patriots and Red Sox memorabilia. Lobster Ale was on tap. A small group of patrons sat at the bar, talking quietly, ignoring the television tuned to a basketball game. They were dressed in working men’s clothes, no doubt on their way home after a day on the job. Hunting season was over, and the weekend snowmobilers hadn’t yet arrived. During the week, between sports seasons, this was a workingman’s bar.

There can be little doubt of John’s occupation. He’s a big man, barrel chested, sporting an untrimmed, month old beard, a plaid woolen shirt and Cardhartt pants. He had just come from work, an almost two hour trip out of the woods. He sipped an oatmeal stout, dark and bitter, a drink that fit his mood.

Border Crossing Building and gate. This gate is closed on Sundays and obviously is not a major crossing. The gate employee declined to speak to me.

John’s workday is long. He rises every workday at 2:30 in the morning and drives twenty-five miles to be at a pickup point at 3:30 AM. He’s then transported two hours into the woods to the logging site. The going can be slow when the dirt roads get covered with deep fresh snow, as they had the night before. At the end of the workday, he retraces his two-hour ride back to the pickup site. John’s wages include only one of the two-hour rides. He usually makes it back to his home at 4:00 PM.

John did not intend to be a logger. He studied forestry for two years. Upon graduation, he set out for the forests of Maine, where he discovered that a two year degree didn’t get you much. So he took up logging. Since that time, he has experienced firsthand the problems other Maine loggers tried unsuccessfully to correct thirteen years ago.

To John, the subject of Canadian loggers working the Maine woods falls like a hot ember on dry brush. He admits to holding bitterness toward a government that, he believes, has abandoned him and other loggers. Yet, it’s apparent his passion has waned. Battle weary or otherwise, the sag in his shoulders belies the glint in his eyes.

He brought with him a folder of news clippings and an op-ed he wrote in a Bangor Daily in the late 1990s. He says the op-ed did not advance his career as a Maine woodsman, where communities are tight and memories are long. He says most loggers don’t complain, fearing it will further reduce the odds of their getting work. Employers also have memories and tend to shy away from any logger with a history of complaints.

“The Canadians even get unemployment from the state,” he added.

“The paper companies run the state,” he says, in a matter of fact tone that doesn’t invite argument. “You have the bonded workers taking our jobs, and the independent contractors that get 1099s and think they’re rich.” “The bonds,” he calls them, depress the wages because of their willingness to work for less money than Americans.

Although, clear cutting doesn’t appear to be a major problem in the north woods, a forester admitted to me that silviculture, the best practice for maintaining a healthy forest, is not used by the logging industry or landowners.

John worked for a logging company for the 2009/2010 logging season, usually mid-summer to the following March. He was the only American on the site. And although a logger’s occupation is fraught with hazards inherent with heavy equipment, soft ground and falling trees, the language spoken on this job site was French. When the season began to wind down in April of 2010, John was laid off. “They laid me off, but kept the Canadians,” he wryly added.

By bonded workers, Miller meant foreigners issued H2-A visas by the federal government. The visa allows foreigners to enter “the U.S. to perform temporary agriculture labor or services of a temporary or seasonal nature.” In this case, the foreigners are Canadian woodsmen. Federal law also places conditions on the hiring of bonded workers: “. . . the employer must file an application with the Department (of Labor) stating that: (1) there are not sufficient able, willing, and qualified United States (U.S.) workers available to perform the temporary and seasonal . . . . employment; and (2) employment of H2-A workers will not adversely affect the wages and working conditions of similarly employed U.S. workers.”

The issue here is the Maine logger’s claim that the job is never really offered to them, or is offered with unacceptable conditions. The system, Miller says, is set up to favor the Canadian woodsman. The reason, of course, is they cost less to hire. Canada has socialized medicine, so health care isn’t an issue of employment. Moreover, because of the U.S.-Canadian exchange rate, Canadian loggers are willing to work for less money, thus setting the wage scale too low for American loggers to survive on.

Depressed wages spill over into other areas of employment. John described an employer he once worked for who agreed to pay him $500.00 a week ($12.50 an hour). When John was subsequently laid off, he discovered the employer had carried him on the books as being paid $250.00 a week for him and $250.00 for his chainsaw. This saved the employer the higher cost of employment taxes but also cut John’s unemployment benefits. John added, “You can’t support a wife and three kids on $125.00 a week.”

As for the legalization of the independent contractor, John describes it as another way for paper companies and mill owners to save money. In the eyes of the law, an independent contractor is a business man responsible for his own business costs.

John: “A kid with no experience can get hired as an independent contractor. The employer doesn’t have to worry about workmen’s comp or employment taxes. He just gives the kid a 1099[IRS form]. He pays the kid $19.00 an hour, a 1099 form, and the kid thinks he won the lottery. The kid never reports the money as taxable income, and the state never checks.” The onus and cost of complying with most state and federal employment laws are transferred to the independent contractor. It’s a win for the employer and a loss for the woodsman.

To gain a better understanding of the H2-A system I spoke to Jorge Acero of the Bureau of Labor Standards, Foreign Labor Certification Unit of the Maine Department of Labor. Mr. Acero explained that when a business expects a need to hire bonded workers for the harvesting season, it will apply for a number of H2-A visas. The applications will be reviewed by his unit and forwarded to the U.S Department of Labor for approval. After this is done, the state of Maine then has no idea who the employer subsequently hires. Moreover, there is no way to track how many Maine woodsmen apply for the job. According to Mr. Acero, most Maine woodsmen do not use email and live in remote areas of the state. If they learn of a job opening they’re likely to apply directly with the employer.

According to Mr. Acero, the State of Maine expects businesses to comply in good faith with state and federal laws stipulating a bonded worker will be hired only after finding there are no U.S. workers available for the job. The state, therefore, expects employers will make a good faith effort to hire Americans for their job openings. However, when asked if any efforts are undertaken by the state to verify employers are in compliance with the law, Mr. Acero explained that due to limited manpower and distances involved, compliance verification is left to the U.S. Department of Labor (USDOL). Indeed, the driving distance from Augusta to Allagash is 288 miles, with a driving time of five hours and forty-five minutes. Then too, there’s the time spent searching the woods for the logging site.

What is left is the question of how does the USDOL follow up on H2-A visa inspections?

A check of Federal offices for the U.S Department of Labor revealed the agency has no office in the State of Maine. In fact, the closest office is in Boston, Massachusetts. I telephoned the USDOL’s Boston office and spoke to Mr. Tim Theberge, a Workforce Specialist. According to Mr. Theberge, H2-A visas are handled by the Foreign Labor Certification Unit. Unfortunately, that unit had moved to Atlanta, Georgia, several years ago. He knew of no USDOL unit currently performing H2-A compliance inspections in the State of Maine. Moreover, in a logging forum that took place in June of 2009, in the northern town of Fort Kent, Maine, Charlene Giles, from the Chicago processing center represented the USDOL.

To gain a better insight into the state’s handling of bonded workers, and at the suggestion of John Miller, I contacted Maine State Senator Troy Jackson. Sen. Jackson is a logger, lives in Allagash and represents Aroostook County in northern Maine. He was also one of the loggers who took part in the 1998 Allagash Blockade.

The senator vouched for much of what John Miller described. However, he added several facts and thoughts of his own.

The exchange rate has “pretty much” evened out and is no longer the primary force driving the hiring of bonded workers from Canada. The senator believes the situation still exists, but the problem has more to do with familiarity than money. Canadian businesses and mills have established a presence in Maine and tend to hire loggers they know, i.e., other Canadians. He cited one instance where a wife opened a business in Maine and brought her husband in as a bonded worker to run it.

The north woods of Maine is also a resource for recreational activities such as hunting, fishing and water sports.

To adjust to the new reality, the Maine legislature passed new laws to protect Maine woodsmen. One of the two eliminates the unemployment benefits for bonded workers. Sen. Jackson explained the situation allowed Canadian loggers to file for unemployment then collect their checks while in Canada, beyond the jurisdiction of Maine to inspect their employment status. The senator spoke of a study that discovered bonded workers collected $600,000.00 in unemployment benefits, while the industry only contributed $200,000.00 to the unemployment insurance fund. Moreover, Maine fell short of due diligence in accepting the applications in the first place. When a person files for unemployment one of the first questions on the application asks if the applicant is ready and able to work. Since the H2-A visa is job specific; a Canadian cannot be ready and able to accept a new job.

The two laws passed are:

An Act To Improve Employment Opportunities for Maine Workers in the Forest Industry: This legislation takes away tax benefits to landowners who use bonded workers to harvest their trees or if they fail to provide required information.

An Act To Protect Maine Workers: This law mandates an employer show proof of ownership for the logging equipment being used. This prevents an employer from leasing logging equipment from a Canadian company to harvest trees in Maine. This makes it difficult for a Canadian to set up a business in Maine and lease his own equipment from Canada. Those opposed to the law point out that also improperly prohibits a Maine employer from leasing the equipment. This puts an unfair burden on employers to purchase expensive equipment. Violations of this law will result in the employer being prohibited from hiring bonded workers for two years.

Yet, despite the passage of the laws, Sen. Jackson is not optimistic that the grievances of the Maine loggers have been resolved. In 2010, he filed ten related complaints with the Maine Department of Labor. At the time of his interview, March 2011, not one has been addressed by that department. “I’m a senator,” he says. “If I can’t get a complaint addressed, how can the average logger.”

He also cited two employers that had, in 2010, been charged with violating state law concerning bonded workers. As of March of 2011, no date has been set for the hearings. The newly elected administration, he says, claims it’s waiting for a new labor commissioner to be appointed. “Why?” Jackson asks. “It’s a straight forward violation of the law.”

Whether his pessimism is based on bad karma or simple irony, Jackson points to Maine’s new Governor, Paul LePage. It is the LePage administration holding up those hearings. A LePage campaign website boasted about his “broad base of experience and knowledge, starting with an executive position with Arthurette Lumber in Canada.” The governor’s connection with a Canadian lumber company does little to instill confidence that positive change is in the offing.

Senator Jackson speculates that another blockade may be needed. This time political promises may not be enough to end it.

In the mean time John Miller sips his stout and quietly reflects on his situation. Life rarely works out as planned. And there is a time to reconsider your decisions. Like Troy Jackson, he expects little change. Demographic realities are hard to overcome. Frustration dings the psyche. There are only several hundred loggers in the state, maybe too small a number to gain meaningful political traction. And that number is going down, as young men look for careers elsewhere. Who can blame them? The forces working against the loggers of Maine may be insurmountable.

John Miller shakes his head. “Next year I’m leaving Maine. Don’t know where I’ll be, but I won’t be here.”